The Civil War veteran and real estate magnate, whose vast holdings included 400,000 acres in Atlantic County, defied the odds in an era of Jim Crow. His estate was valued at $2 million, roughly $52 million today.

“I look at John McKee as the forerunner of black entrepreneurship in this country,” said Ralph Hunter, founder and curator of the African American Heritage Museum of Southern New Jersey. “He was so far ahead of the curve.”

Even in death, McKee held the reins of an empire that included 400 properties in Philadelphia; 66 acres along the Delaware River north of the city; 23,000 acres in New York; and some 300,000 acres of coal, oil and farm land holdings in Georgia, Kentucky and West Virginia.

In a sprawling 27-page will, he set forth a plan to continue developing McKee City, an area of Egg Harbor and Hamilton townships that still bears his name.

Revenue from 999-year leases in South Jersey would help fund the “Colonel John McKee’s College,” a school for orphaned boys, regardless of race. He also set aside 10 acres of land for the Catholic diocese, which would eventually be used for St. Katharine Drexel parish.

McKee was less generous, however, with his own family, bequeathing a gold watch and $50 annuity to his grandson and free rent at a small cottage and a $300 annuity to his surviving daughter.

Few of McKee’s plans ever came to fruition due to legal wrangling over his will, but historians say the document sheds light on a mysterious and influential figure. Newspapers reported the family drama, but contained little information about the man himself.

“It’s like nobody has quite figured the megalomaniac out,” said Atlantic County historian June Sheridan. “He’s an enigma, this person you can’t quite put your thumb on.”

McKee was born to free black parents in Alexandria, Va., around 1821 and was indentured to a brick maker as a young man. At 21, he came to Philadelphia and worked a series of service jobs before marrying the daughter of James Prosser, a wealthy black caterer and restauranteur.

In 1863, he enlisted with the 12th regiment of the U.S. Colored Infrantry, where he served until the close of the war. After the war, McKee entered the real estate business, renting houses and leasing farm land to the influx of freed slaves that came north.

Sheridan said there’s little indication of how he was able to purchase the properties, but it’s likely he used his father-in-law’s wealth as a springboard. According to census records, McKee’s real estate holdings grew from $15,000 to $190,000 in the 10 years between 1860 and 1870. In 1860, his 12-member household included a coachman, servant and waiter, luxuries few families could afford then or now.

Whatever the source of McKee’s seed money, he became known as a shrewd businessman and meticulous boss. His leases stipulated exactly what could be built on the property, how the land should be cleared and even which crops his tenants should grow each year.

“There’s a real question about whether he was doing a good thing or if he was taking advantage of (free slaves) because they were susceptible,” Sheridan said.

McKee’s secrecy led to speculation about his motives.

Mitchell Hopkins, an elderly McKee City resident who had worked for McKee maintaining properties, was quoted in a 1937 Atlantic City Press article saying he believed his employer “made much of his fortune in the slave trade.” He added that McKee came to Atlantic County about once every two weeks to direct construction and the clearing of land.

Hunter said it’s likely McKee faced resistance as he bought large tracts of Atlantic County in the 1880s. By the time of his death, his land holdings dwarfed the built-out area of Atlantic City, accounting for slightly less than 1 percent of the county’s total land area.

“It was unheard of to think of an African-American man who could put together a fortune of this magnitude in that period of time,” he said.

Well into the 20th century, Hunter said blacks in New Jersey often used “straw buyers” who would purchase property and transfer it to their name.

McKee may have had an easier time than most because of his Gaelic surname and light skin — his grandson T. John McKee, a prominent Wall Street attorney, for decades “passed” as a white man — but the historical record is sparse.

By 1902, McKee City had a population of 185, many of them ex-slaves. The community, which centered on the railroad, boasted a general store, post office and school.

In the will, McKee instructed his executors — including Catholic Archbishop Patrick Ryan, who reportedly had never met McKee prior to being notified of the bequest — to continue developing

McKee City. Tenants would be required to build “a substantial brick or frame dwelling house containing not less than six rooms” and could purchase their properties after the expiration of a 999-year lease.

In an attempt to ensure his legacy, McKee stipulated that all deeds show the parcel located was in “McKee City.” The name has stuck, but these days the designation is informal.

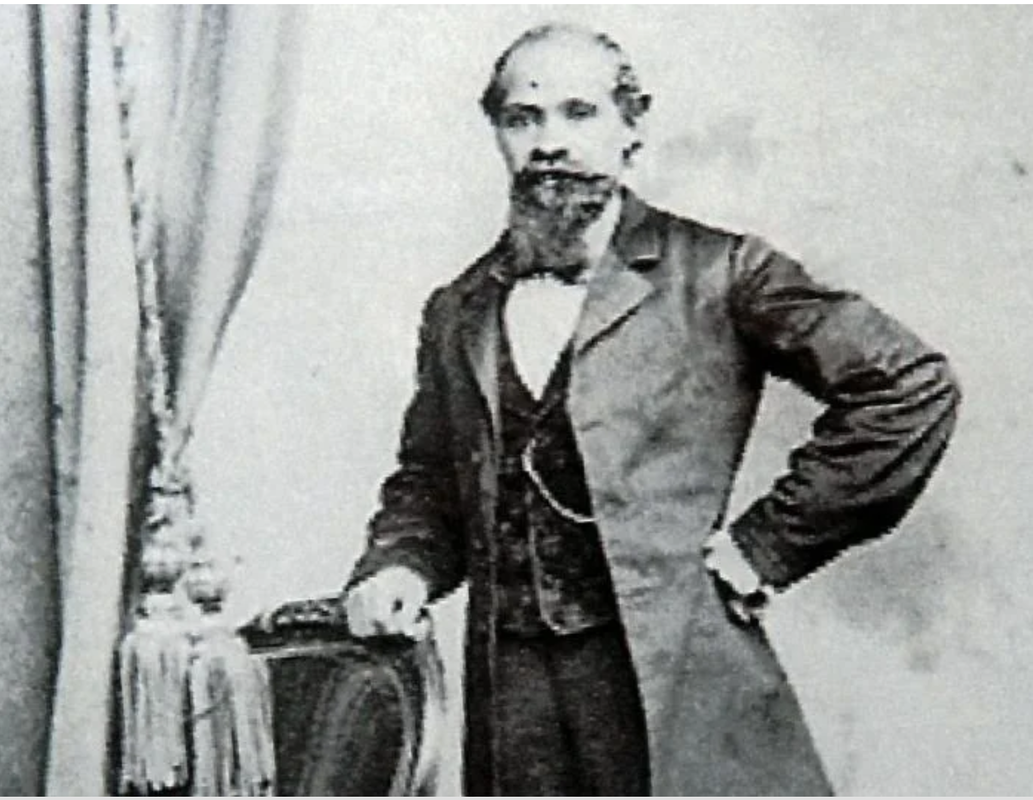

Similarly, McKee’s school for orphans would prominently feature a statue of him mounted on a horse. McKee helpfully included a photo of himself in his Civil War uniform in the envelope when he was drafting the will in 1899.

“He was creating a tribute to himself,” Sheridan said. “I don’t know if it was ego or if he really cared about the college; he never let anyone know what his reasons were.”

Today, little remains of McKee’s city. Many of the original buildings burned or were torn down in the intervening century. Part of the land holdings became what is now the Atlantic City Race Course and the Hamilton Mall.

Bill Boerner owns the last remaining farmhouse from McKee City, which his family purchased about a century ago. He still grows apples and other produce at his Pleasant Valley Farms off Route 40 in Hamilton Township.

“People don’t even know what McKee City is anymore,” he said. “It got gobbled up by the shopping developm

While the college envisioned never materialized, a 1952 court settlement did result in scholarship program that still awards about $250,000 to between 15 to 20 college-bound orphan boys each year.

Robert J. Stern, the McKee Scholarship Fund’s executive secretary, said the fund has about $5 million in invested assets. The scholarships are rewarded primarily from the earnings of that money, not the principal, he said.

“Fatherless boys already have one strike against them and sometimes more,” he said. “It’s a great thing for their education, especially with the government cutbacks in education.”

ents.”

- By WALLACE McKELVEY Staff Writer

- Feb 24, 2013

RSS Feed

RSS Feed